Ethan’s Legacy: A Life that Mattered

IN JANUARY 2013, 26-year-old Ethan Saylor went to see Zero Dark Thirty with his aide, Mary, at a movie theater in F rederick County, Maryland. After the movie ended, Mary left to get her car, and Ethan went back into the theater to watch the movie again. When the theater manager asked him to leave because he did not have a ticket, Ethan refused. The manager called police — who dragged Ethan from his seat, while Mary warned them this would startle Ethan and begged them to let her handle the situation. In the final moments of struggle, Ethan cried out for his mother as the police officers fractured his larynx, suffocating and killing him.

In the years following her son’s death, Patti Saylor galvanized the disability community. She spurred a push in Maryland for law enforcement training that rejects biased stereotypes and adopts best practices for how officers interact with people who are differentlyabled. The model she helped develop enlightens first responders while empowering the people they are sworn to protect.

VULNERABLE VICTIMS

When Saylor first began researching how to implement training programs, she looked for information about how man y other deaths like her son’s could have occurred at the hands of law enforcement.

Unfortunately, she discovered that there are no reliable statistics for such incidents. However, it is evident that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are four to 10 times mor e likely than others to be victims of crime, according to The Arc, a national

IDD advocacy organization.

People with IDD are also at risk of being suspected perpetrators — an assumption that can have fatal implications. Former institution chaplain and disability advocate Robert Perske has analyzed false confessions among people with IDD for decades. He has found at least 75 instances in which individuals with IDD were coerced into confessing crimes they may not have committed. Sadly, at least five were executed. And although individuals with IDD comprise approximately 3 percent of the U.S. population, they make up as much as 10 per cent of the prison population, according to The Arc.

BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS

In discovering the lack of information and resources available for this area, Saylor determined education was the first step. She started by bringing better training to Maryland. In 2015, a new law established the Ethan Saylor Alliance for Self-Advocates as Educators, a government entity that operates under the Maryland Department of Disabilities. In 2017, the alliance’s training program was voluntarily adopted by law enforcement agencies throughout the state, and now all new cadets ar e required to participate.

In a groundbreaking approach, each training session is led by selfadvocates, who learn how to become educators through a program developed and hosted by Loyola University Maryland, Prince George’s Community College Municipal Police Academy, and Best Buddies Maryland. Having self-advocate educators included was crucial to the training’s success, Saylor notes.

“To me, having relationships with people with IDD and getting rid of stereotypes is the training,” she adds. “If the law enforcement officers in Ethan’s case had actually had a relationship with a person with Down syndrome, they would be coming from a different place. They wouldn’t automatically think, ‘This is a criminal act.’”

PAVING THE WAY

Currently, no national requirements exist for how U.S. law enforcement officers should be trained to interact with people with IDD. The U.S. Department of Justice and private organizations, such as the International Association of Chiefs of Police, have created training programs and best practices, but implementing them is not mandatory. Complicating matters, the entities that govern and set training requirements for police departments vary from state to state, according to Saylor.

Still, Ethan’s death shed renewed light on the need for better, mandatory training. Many organizations are launching or reinvigorating grassroots efforts to prevent further misinterpretation, coercion, and deaths.

For example, The Arc of Aurora (Colorado) has been working with local law enforcement for 10 to 15 y ears, according to Jean Solis, Manager of the chapter’s “THINK+change” program. “THINK+change” has partnered with the Aurora police department to develop online IDD training materials and hold in-person sessions that focus on how to communicate with crime victims who have IDD. “THINK+change” has also developed online training programs for the Colorado District Attorneys’ Council.

Lloyd Lewis, President and CEO of the Colorado-based arc Thrift Stores, has seen the program’s impact statewide.

“This whole era of presuming that people with IDD aren’t reliable, aren’t giving accurate statements, is being diminished in Colorado, and there’s better interaction with law enforcement,” he says.

Another innovative approach to improving relationships with law enforcement is “Growth Through Opportunity (GTO) Cadets™,” based in Roanoke, Virginia, and founded by retired law enforcement officer Travis Akins. The program pairs self-advocates with first responders through job training. The Cadets perform office duties — dressed in uniform — and receive job coaching, all while building relationships with, and in their own way, “training,” first responders. “GTO Cadets” has expanded and now partners with 24 public safety agencies in Virginia and Minnesota.

“Ethan Saylor’s tragedy was definitely a launching pad … to wake people up all around this country,” Akins says. “If a young man with Down syndrome can be killed in the hands of police in a movie theater, while having an aide, it can happen to anyone.”

While we honor the hard work Saylor and other organizations have done on this, there is still much work to be done in educating la w enforcement. This past August, a young man in Sweden named Eric Torell, who had Down syndrome and autism, was killed by police because they thought a toy gun he was carrying was real. The fight for inclusion, awareness, and education continues.

A LIFE THAT MATTERED

A LIFE THAT MATTERED

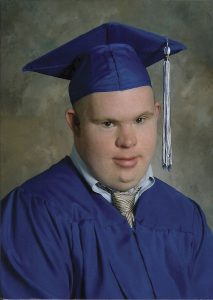

Ethan Saylor, at 26, was the oldest of three children. He attended community college and was fascinated with law enforcement. He never faltered in being “a good big brother,” his sister, Emma, told The Washington Post.

After a grand jury in Maryland failed to indict the deputies who killed her son, Ethan’s mother, Patti Saylor, filed a civil lawsuit on his behalf. Last April, when she accepted $1.9 million to settle the case, she told The Washington Post, “We’re not comforted by the money as much as knowing we gave our son everything we could — that we stood up for him until we exhausted all avenues for standing up for him, because his life mattered.”

STEP UP FOR CHANGE

Patti Saylor offers these strategies for getting intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) training implemented in your area:

- Identify which state or local entity sets the training standards for your local law enforcement. Find out if IDD training is mandatory.

- Establish relationships with local law enforcement. For example, invite your sheriff to attend a local Down syndrome organization meeting.

- Work with your local Down syndrome organization (or other disability advocacy group) to introduce training curricula to the appropriate entity.

“Local organizations should bring in best practices, not just what they think officers should know, because that’s when we see bad training,” she says.

Saylor recommends professionally developed programs, such as The Arc’s “Pathways to Justice®,” which is available for free. Details can be found at thearc.org.

Also recommended is BE SAFE The Movie, a DVD available at besafethemovie.com. It teaches people with IDD and their parents or caregivers how to interact with police and what to do in emergencies.

This article was published with permission from Global Down Syndrome Foundation.